India

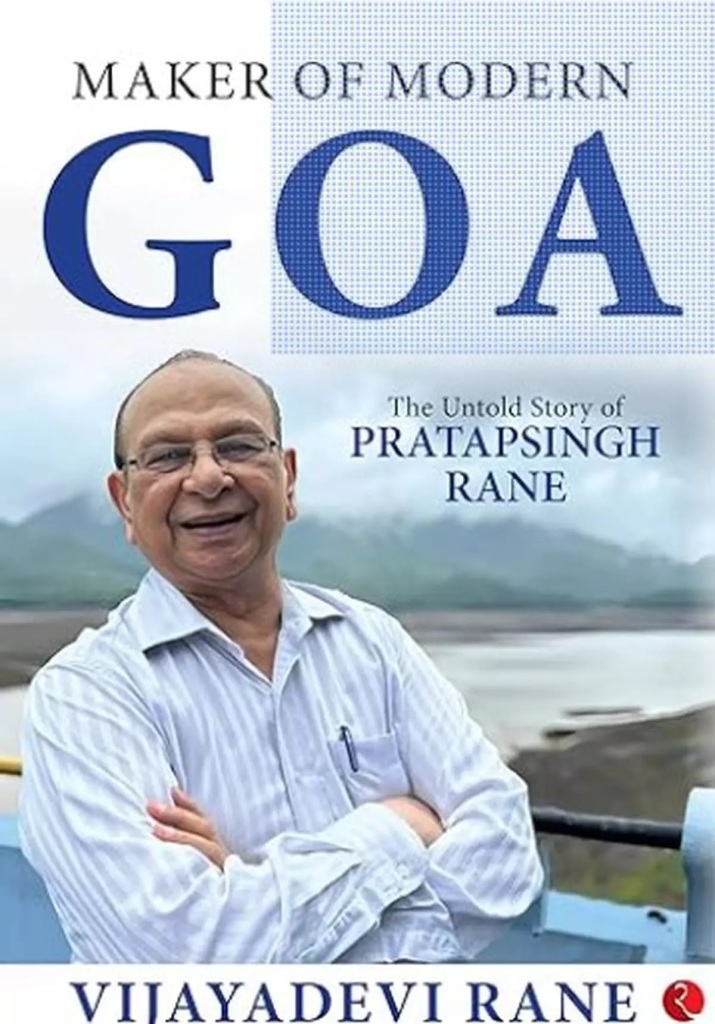

Maker of Modern Goa: The Untold Story of Pratapsingh Rane

An absorbing chronicle for anyone interested in the many layers of Goan history and politics By Shailaja Chandra

By Shailaja Chandra

Updated – April 12, 2024 at 01:59 PM

When the man’s biographer is his wife, one can be certain the story would be laudatory. And that is what Vijayadevi Rane’s recent book – Maker of Modern Goa – the untold story of Pratapsingh Rane, clearly is. But happily, it goes well beyond, making the book an absorbing chronicle for anyone interested in the many layers of Goan history and politics.

The elegantly draped hardbound book is mostly about Rane, the man who never lost an election in 50 years, and remained Goa’s Chief Minister for over five cycles. But sprinkled with elements from Portuguese, Goan Catholic and Hindu ethnicity, the narrative becomes complex but thereby more interesting.

Starting with Goa’s first CM –Dayanand Bandodkar, who inducted Pratap Singh into politics, there are countless stories about the Rane clan and their close association with the erstwhile Scindia royal family of Gwalior. Pratap Singh’s almost soldierly schooling, his professional degree in business management acquired in the United States, his engagement by a corporate set up, (Telco) and how he was abruptly thrown into the hurly burly of Goa’s political affairs to become the Chief Minister many times over, has been told simply but engagingly.

The narrative is a valuable backdrop which both residents and visitors to Goa will enjoy. There is much to learn about the subjugation and forced conversions inflicted by the Portuguese rulers, the fierce combats that ensued, the refusal of some, like Rane’s ancestors, to accept suppression, the rise of the bhatkar class (landowners) and the role of Bandodkar, the man whose name springs into the book nearly 40 times. The political tumult against the ruling elites – the Goud Saraswat Brahmins and the Portuguese-Catholics – and the liberation of Goa in less than 24 hours enhance one’s understanding of Goa as it was then. The part played by the erstwhile Prime Ministers of India and the visits of several celebrities provide kaleidoscopic images of a slew of important events which go well beyond the title of the book.

Along the way, one learns that Rane was an equestrian medal winner and a horse racing jockey several times over, plus an accomplished boxer – something he never divulged to the stream of civil servants, each of who knew Rane well. Despite being born to privilege and destined to lead a polished if not plush life as a top corporate executive, overnight Rane found himself having to return to tend to his father’s estate in agrarian North Goa- where even today the family continues to live in the same family home.

Several civil servants who worked closely with Rane in the 1980s (including myself) have recounted how much development and good governance mattered to Rane– a refrain which resonates throughout the book. Those recollections exhibit how a politician who is direct in his dealings, liberal in his approach, and thoughtful and caring in action can still win elections and retain power. Albeit in India’s most educated, most affluent, and well-liked state – an unmatched gem in a gigantic country.

During my Goa years, I had many opportunities to watch the author, Vijayadevi, at close quarters. Her charm and scintillating laughter remain vivid memories even today, but her book presents a narrative which she seldom alluded to when she was the CM’s wife. The Rane couple, however, emerge exactly as they were then – urbane, sophisticated, upper-class – even royal – but with core attributes of modesty, courtesy, and kind-heartedness. Rane’s style of administration – spending time understanding things, establishing communication channels with those likely to be affected, his organisational abilities, and the complete absence of arrogance have been captured with illustrative stories which ring true.

While the narratives of family history provide a detailed account of who married who amongst the erstwhile royal families of Gwalior in MP and Sandur in Karnataka, it is the machinations of Goan politicians and their self-serving brand of politics which often take centre-stage.Those events are important to understand Goan politics but minus knowledge of the dramatis personae involved, the stories of how Pratap Singh was overthrown by his political rivals, how he returned to power,only to lose or win it back, might faze a casual reader. Fortunately, the book has much more to offer than that muddied history.

More appealing are the recollections of legendary Goans – vocal maestros like Kesarbai Kerkar, Kishori Amonkar, Lata Mangeshkar, the tradition of temple performers and all-night concerts — a world which stands apart from the feisty notions many visitors carry of Goa. The contributions of Master painters like Francis Newton and V S Gaitonde find their place in the narrative, as does that of the eminent Goan architect Charles Correa who designed that haven of art and culture – the Kala Academy. Rane remained the chairman of Kala Academy for nearly three-decades and fiercely guarded it from politics. He was witness to Gyani Zail Singh, the then President of India stomping out of Goa’s 25th anniversary of liberation celebrations because Lata Mangeshkar declined to sing at Mahamahim Rashtrapatiji’s request.

In one sentence, Vijayadevi was the talisman that buoyed up Pratap Singh’s political and personal life. And made this tale worth telling- and reading.

(Shailaja Chandra was a career civil servant for almost 40 years having held assignments in the Central Government in the Ministries of Defence, Power and Health. At the state level, Ms. Chandra was posted in Manipur, Goa and the Union Territories of Delhi and the Andaman & Nicobar Islands).

The stories that show how India administered 100 crore Covid vaccines

Shailaja Chandra writes: They demonstrate great resilience, ingenuity and persistence. The momentum must not flag as the war is far from over

![]() Written by Shailaja Chandra |Updated: October 27, 2021 7:48:39 am

Written by Shailaja Chandra |Updated: October 27, 2021 7:48:39 am

This article is a candid account of where we stand, having just crossed the stupendous 100 crore vaccination milestone. Some verifiable stories of grit and ingenuity will show how difficult it was.

Six factors are majorly responsible for last week’s achievement. First, all states were eager to immunise eligible citizens. That matters. Second, India had the manufacturing capacity to produce the vaccines. Most of the world does not. Third, despite avoidable confusion around May, once the central purchase of vaccines for those above the age of 44 commenced, the process of procurement, cold chain upgradation, logistic planning and online training of vaccination teams (cascading down to millions of health workers) was executed splendidly across both the public and private sectors. Fourth, every jab was linked through the Aadhaar card to the CoWin app, making tracking easy and fudging impossible. Fifth, local teams showed imagination to overcome enormous geographic obstacles. Sixth, there was unanimous public support — crucial for success.

First, the big picture. Goa, Himachal Pradesh, Sikkim and the Union territories of Chandigarh, Jammu, Kashmir, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Lakshadweep and Dadra and Nagar Haveli (DD & H) have achieved 100 per cent vaccination. Their smallness must not diminish the success of complete immunisation executed in the most inaccessible habitations. Reaching small, isolated groups of tribal people living on different islands in the Andaman archipelago and persuading them was far from easy. Up north in mountainous Himachal Pradesh, hundreds of minuscule settlements dotting the mountain cliffs, visible only from a helicopter, had to be reached somehow. In the west, the tribal people of DD &H, mostly unseen, living within forest groves, had to be located and jabbed. Achieving 100 per cent immunisation in such inaccessible pockets was not tiny.

Among the large states, Kerala, Uttarakhand, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and the UT of Ladakh have achieved 90 per cent coverage with the first dose. The story, however, is not very encouraging for Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Jharkhand, and the Northeastern states of Manipur, Meghalaya, and Nagaland where only 65 per cent of the population or less, have been vaccinated with the first dose. This is worrying because the populations of UP, Bihar and Jharkhand alone represent one-fifth of India. The remaining large states fall somewhere between the 65 per cent and 90 per cent levels and the speed of immunisation does not appear to be in top gear. In fact, the CoWin app clearly exhibits how tardy the offtake of the second dose has been — almost everywhere. Summing up, a little more than 30 per cent adults are fully vaccinated, about 45 per cent have received only one dose and 25 per cent have not had even one dose.

Even so, behind millions of successful inoculations lie stories of great resilience. Examples from two high-performing states illustrate this. Madhya Pradesh has only half the population density of the national average. The state is home to 46 tribal groups. Mohammed Suleman, the state’s additional chief secretary (health), told me, “We realised that even as the urban areas were getting saturated, the rural areas were lagging. The district administrations then identified schools and community halls in every settlement, following the electoral polling booth strategy. Based on detailed mapping, each district scheduled outreach camps for two days for each hamlet falling within the gram panchayat. Each team had to vaccinate 5,000 adults within two weeks. One example will explain the challenge. Gawaria Faria hamlet has just 400 inhabitants. It falls in Sogat village, located some 60 kilometres from the Alirajpur district headquarters. Reena Sengar, the local auxiliary nurse midwife, led the team on an 8-kilometre uphill trek after which they camped in a primary school. They conducted scores of vaccinations each day, which is the story of hundreds of interior villages in Madhya Pradesh.”

Amitabh Avasthi, the principal health secretary in Himachal Pradesh, recounted an experience involving vaccine hesitancy. The people of Malan, a remote village in Kullu district, had refused vaccination until their deity (devta) agreed. The Deputy Commissioner walked for six hours to personally convince the deity. After much persuasion, the devta finally approved, after which 1,000 people got vaccinated in a single day. In another village Bara Bhangal, unconnected by road, the DC requisitioned the state helicopter to enable the vaccines to be administered.” Avasthi, however, added, “Without support from the Gompas (religious leaders) and his Holiness the Dalai Lama, it would not have been possible. Himachal’s 100 per cent vaccination was rewarded with special congratulations from the PM.”

If remoteness in India is a challenge, so is population density. The Mumbai Municipal Commissioner I S Chahal told me, “Mumbai reached close to 100 per cent single-dose vaccination by adopting a unique model. BMC’s tripartite Memorandum of Understanding with the corporates, the private hospitals and the Corporation resulted in free vaccinations being administered by private hospitals to 10 lakh slum-dwellers. That helped.”

In Delhi, with a population of over 25 million, Monica Rana, director, family welfare, explained, “Delhi has covered more than 85 per cent of its adult population with at least one shot and 46 per cent with two shots. With thousands of unorganised pockets, it would have been impossible to provide vaccination services within walking distance. Take, for example, a densely populated area like Mohan Garden in southwest Delhi, with a population of around 1.2 lac people. We had to operate six vaccination sites simultaneously every day using two local schools to vaccinate more than 1,200 people on a good day — all within walking distance.”

Battles are being won every day. But the war is far from over. Presently the CoWin app displays huge peaks and troughs state to state and week to week. In the last few weeks, the vaccination numbers have fallen steeply everywhere. Whatever the reasons — festivals, vaccine availability, organisation, staff or something else — maintaining the momentum will be the biggest challenge for India’s vaccination drive.

A billion jabs have rightly given cause for celebration. While saluting everyone who had a hand — big or small — in this feat, it is good to remember that we have miles to go before we sleep.

This column first appeared in the print edition on October 27, 2021 under the title ‘Taking vaccines to the people’. The writer was former secretary, Health Ministry

Mainstreaming & Integration of AYUSH in the Indian Healthcare System

3rd Webinar in the TDU-IPH-JNU Webinar Series.

3rd Webinar in the TDU-IPH-JNU Webinar Series.

“Mainstreaming & Integration of #AYUSH in the Indian Healthcare System”

The University of Trans-Disciplinary Health Sciences and Technology was live.

8 February at 21:35 ·

Shailaja Chandra on developing a transformative healthcare system for India

Standpoint

Standpoint

Shailaja Chandra on developing a transformative healthcare system for India

Former Secretary to the Government of India and former Chief Secretary, Delhi Ms. Shailaja Chandra, in conversation with Arghya Sengupta (Research Director, Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy) and Shruti Kapila (Faculty of History, Cambridge South Asia Institute) on the challenges to building a transformative healthcare system in India and why the government doesn’t spend enough on health. Listen in to episode 5 of our ‘Standpoint’ podcast series, jointly brought to you by the Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy and the Cambridge Centre for South Asian Studies in association with The Times of India.

Source: Vidhi Centre for Legal Policy, Cambridge South Asia Institute, TNN

The Big Picture – Lifestyle diseases biggest health risk for Indians

Rajya Sabha TV Published on 15 Nov 2017 | RSTV

Guests: Dr. Puneet Misra, Professor of Community Medicine, AIIMS; Shailja Chandra, Former Health Secretary, Government of India; Dr. Shridhar Dwivedi, Senior Consultant, National Heart Institute

Anchor: Frank Rausan Pereira

Innovation, information and institutional change, next challenges for gender equality

interview from key speaker Shailaja Chandra, Former Exec Director National Population Stabilization Fund Government of India, talk about policy related to womens rights at the OECD/UNESCO International Workshop Gender Equality and Progress in Societies 12 March 2010.