malnutrition

The Big Picture – War on Malnutrition and Poverty: Welfare schemes helped?

Guests: Shailaja Chandra (Former Health Secretary, Government of India) ; Pamela Philipose (Development Journalist) ; Reetika Khera (Associate Professor) ; Vipul Mudgal (Project Director, CSDS) and Anchor: Girish Nikam

Air date: October 16, 2014 (Rajyasabha TV)

I come in at 1:53 Minute, 6:50 Minute, 13:48 Minute, 23:15 Minute & 26.15 Minutes.

Swacch Bharat, opportunity to do things differently

That the Union government has accorded high priority to ‘swachhata’ deserves cheer. But lest it is forgotten, previous governments had also given similar priority to sanitation under the aegis of the “Total Sanitation Campaign” which started in 1999. Although the 15-year graph of toilets constructed by the states is impressive, it has, nonetheless, left nearly half of India defecating in the open.

That the Union government has accorded high priority to ‘swachhata’ deserves cheer. But lest it is forgotten, previous governments had also given similar priority to sanitation under the aegis of the “Total Sanitation Campaign” which started in 1999. Although the 15-year graph of toilets constructed by the states is impressive, it has, nonetheless, left nearly half of India defecating in the open.

The ministries of drinking water and sanitation, and urban development, the World Bank, UNICEF, prominent bilateral agencies, philanthropists and countless NGOs have been trying to get Indians to build and use toilets through all these years.

Yet, the census shows that rural sanitation is just 31 per cent and Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Odisha, Bihar, Rajasthan and Uttar Pradesh (in that order) are among those with the worst standard of sanitation. It is not as though the educated South is much better as Tamil Nadu and even Karnataka have far to go, having fallen behind the national average. Toilet use in urban areas in the country is better but still lags far behind the standards of poorer countries like Bangladesh.

Over the years, the Ministry of Drinking Water and Sanitation has judged success of the programme by the number of latrines built and the number of villages awarded the Nirmal Gram Puraskar for becoming open defecation-free.

This, despite the known fact that money spent on spreading awareness and building toilets has often led to highly unsatisfactory utilisation outcomes, exacerbated by the lack of water and astonishingly, an individual preference for open defecation.

The Swacch Bharat programme, therefore, presents an opportunity for doing things differently — but only if the challenges are confronted imaginatively and not by short-lived attempts to wield the broom before cameras. And if the new programme is implemented without rewards and retributions for key functionaries and citizens, this too will become like many other bureaucratic ventures — banal and boring.

Starting June this year, a slew of international articles supported by research papers from public health experts hammered India for failure to contain open defecation, exacerbated by a burgeoning population prone to malnutrition, stunting and succumbing to diarrhoeal diseases.

Public health reports have been unanimous in showing how bacteria and worms get ingested through the faecal-oral route, largely the result of open defecation and unhygienic disposal of human excreta. As a result, it is the most vulnerable – mainly young children – who become incapable of absorbing calories and nutrients and are rendered victims of malnutrition, stunting and diarrhoeal diseases.

The use of toilets must therefore be monitored without using the right tools and asking the right questions: whether there was a decline in water-borne diseases after a village got access to toilets? Did deaths of children under 5 (the most at-risk segment) reduce? Did malnutrition levels come down? The health ministry’s expert institutions conduct surveys on all these subjects but as long as sanitation is considered to be another department’s responsibility, issues of turf will prevent fresh thinking and reporting.

Swacch Bharat can sweep out decade old mindsets and augur in a new way of judging success and equally failure. But that requires a shared vision to improve health indices as the first priority and not let sermons and construction statistics detract from the primary focus.

Access to sanitation

While urban areas may look better placed compared to rural areas as more than an 80 per cent provision of toilets is reported, the capital city of Delhi (one of the better cities) has considerable open defecation. Social studies show that people feel that squatting is for free and the disposal of excreta flowing into water is “clean business”.

In any case, the daily defecation into the Yamuna is considered a miniscule addition to the huge quantities of untreated sewage which have already choked the river for years. Importantly, slum households living besides the riverbed do not consider access to sanitation among their top list of household priorities (TVs and mobiles matter more).

But swatchhata is not only about latrines. It also includes towns and cities with clean surroundings, where debris, garbage and construction rubble make the citizen’s life miserable. No miscreant ever gets fined for creating a nuisance even as the municipal staff and police jointly lament that the fines are too low and the possibility of punishment too remote for citizens to be deterred.

That being so, whether it is rural India or urban, the Swachh Bharat programme needs to make structural changes in the way supervisory responsibilities are apportioned. Sanitation outcomes need to be judged by factors which are germane to the fundamental aim of sanitation which is to promote public health and improve civic conditions.

In rural areas, reducing diarrhoeal outbreaks, malnutrition and under-5 child deaths should become essential end- products of the sanitation campaign as much as the construction of toilets itself. Open defecation must be viewed by society as something intolerable, to be spurned by all.

The invocation of the Mahatma’s name and our ancient adages about swacchata may not motivate poor households as much as economic solutions like night-soil based bio-gas plants (which are functioning in villages in Pune district supplying cooking gas to households) might stimulate change.

When it comes to urban spaces, fines must be raised drastically by altering the schedule to the Municipal Corporation of Delhi Act is something the urban development ministry can authorise overnight. Making the fine payable on-the-spot or by having to appear before an executive magistrate who can triple the fine or add it to the property tax bill in case of default would have visible impact.

It is time swachhata was judged by healthier, safer lives and not just by counting latrines. Two key ministries have a great chance to do things differently.

The Older They Get, the Bolder They Get: 2

FIRST STIRRINGS:

‘Life is not a bed of roses, roses also have thorns’

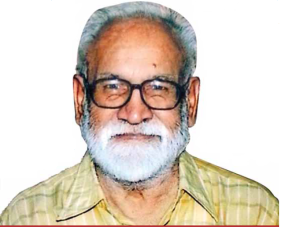

TWO months ago, when I set out to write about unusual retired civil servants, I hunted for suggestions. An IAS officer, generally known for his acerbic tongue and derisive comments, told me to write on SS Jog, a former Director-General of Police in Maharashtra. The suggestion itself was atypical; when I discovered that Jog had settled down in Amravati, I sensed an unusual story.

But, getting hold of Suryakant Jog was not easy. At 87, he does not use email and his hearing is also now impaired. So, I had to find some other way of getting an authentic story. Decorated with an array of medals, including three President’s police medals — for distinguished service, for gallantry and for meritorious service — and the Asiad Vashishta Sewa medal, Jog is off the radar of Google and Wikipedia. Anyone who has remained so modest must have some stuff, I thought.

Jog did his schooling in the local municipal school followed by college in Amravati. He only moved to Nagpur for post-graduation in chemistry and stood first in the university. But, his accomplishments as a sportsman sound even more impressive. To have represented Madhya Pradesh in the Ranji Trophy and the Governor’s XI is no mean feat. When the Commonwealth XI cricket team toured India and Pakistan in 1949-50, the team played 17 first-class matches. SS Jog was on the first and second Commonwealth XI teams as well as the India XI team. Simultaneously, he represented the state of MP in football too.

After he joined the IPS in 1953, securing the third rank, his early years were spent in Madhya Pradesh at a time when Maharashtra state was yet to be formed. After an initial posting as SP, Buldhana, he moved to Sambre, then in Karnataka, where he was drawn into the Goa liberation movement. He proudly recalls: “For services rendered before, during and after Operation Vijay, I was given the police medal in the 9th year of service — an exception.” Soon after, he was appointed Secretary to the Lieutenant Governor of Goa, where he had to also function as the Exposition commissioner for the relics of Saint Francis Xavier. The mortal remains of the saint, who died in 1552, are kept in a casket in the Basilica of the Bom Jesus church in Old Goa. Every ten years, they are brought out for closer public viewing. At that time, thousands of devotees from all over the world congregate to pay homage, a huge challenge for the little township of Panaji.

Jog’s first posting in Maharashtra was as the Superintendent of Police in Aurangabad, which was, in his view, an eye-opener. A district, which was recognised for communal harmony, saw an unexpected flare-up. Local politicians got him bundled out. Having attended his farewell party, he was half-way to Akola district to join his next posting even as his successor was about to reach Aurangabad. When he was midway, orders came, directing him to go back to Aurangabad. The Chief Minister had given in to a counter public demand not to transfer the SP.

Jog’s postings in the city of Bombay (then) were for him the best years of his career in many ways. He handled all key assignments any policeman looks forward to: as in-charge of pecial Branch, Crime and Traffic. The Bombay Police was kno n the world over for its efficiency and discipline. He attributes his own success to two factors: a great Chief Minister, Vasant Rao Naik, and loyal subordinates.

With a change of Chief Minister — after Yashwant Rao Chavan became the CM — Jog found himself moved from one unimportant assignment to another. A posting on central deputation brought nothing better until he was appointed Joint Secretary in charge of Police, in the Ministry of Home Affairs. He makes an interesting observation: “In the police, seniority and hierarchy overtake everything, whereas the Cabinet Secretary (an ICS officer) would ask my opinion directly when I was a mere Joint Secretary.”

After Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s assassination in 1984, Jog was appointed the Police Commissioner of Delhi. He was the first to argue that the job should go to a cadre officer, but was overruled. Unfortunately, the high-profile posting was not propitious for him as the ensuing years brought him neverending grief. Soon after taking over as Police Commissioner, his wife began to be treated for an illness that seemed to have no diagnosis. After six months he was posted back to Maharashtra as the State DGP. The first shock came a few months later when his 23-year old son, his youngest child, crashed while flying a MiG-21 at Tezpur. That was 1985. A year later, some say to that very day which was October 3, his wife succumbed to cancer.

ANAMI Roy was DGP in Maharashtra some 20 years later. He had this to say: “I worked as the AIG directly attached to Jog sahib. I was his staff officer. I was present when his wife died on exactly the date of his son’s first death anniversary. For some time the DG stayed at home, but returned on one condition which he put to me as his staff officer. If he passed any order which was harsh or uncharacteristic, I was to withhold the file and resubmit it as he did not want his decision-making to be clouded by his own mental agony.”

Roy adds, “Jog sahib was a methodical person. A bit scary, because he had a photographic memory and could recall facts, figures, faces and even numbers from 20 years before when he too worked as staff officer to the then DG. I have seen so many magnetic personalities in the police service. Some were born leaders, usually larger than life — they seemed to command things to happen without doing much personally. Jog sahib was different. Meetings lasted just a few minutes when his memory would swivel back to exactly the file, the precise noting, the exact year, when something relevant took place — whether it was a law and order matter or a police investigation. You had to be perfect with facts when you faced him. But every time I came out of his room, I came out wiser. Every minute with him was a learning experience.”

When Jog retired, he sought nothing from the government; nor did he look for benefactors in the private sector. Instead, after 38 years he returned to Amravati. “What is so great about going back to your hometown where you already own a house?” a Maharashtra colleague, with whom I discussed Jog’s story, asked me.

But a glance at Amravati (map on next page) shows just how far this district is from Mumbai. That it is among the 12 backward districts of Maharashtra and has been receiving funds from the central Backward Regions programme, is an indication that Amravati is no land of bounty. How many of us have retired to anywhere excepting the state capitals, I thought.

Jog too had initial doubts about Amravati; only circumstances willed otherwise. As he puts it: “I expected to find many friends but discovered they had all moved away. I wondered whether I had made the right decision in coming here. I spent my nights scribbling what I could do to make a difference, only to score it out the next morning. One day I decided to find a way to engage youngsters. I started organising youth camps in Semadoh village, which is located in the dense Melghat forest, by taking advantage of my police connections. My aims were three: Push them to become adventurous; implant a sense of discipline and instruct them about forests and wildlife. My greatest achievement was that I spurred them to do it. If they scaled 10 feet in a day, they yearned to reach 20. A 10-kilometre trek was never enough for them, they had to double the record that very day. The camps were a great success, but critics doubted what could be achieved in 15 days, the duration of each camp. I told them that every young man was selected after an interview and, at the end of the camp, each one got a sense of pride and discovered his potential. My financial burden was greatly reduced when the Central scheme for youth affairs began to extend support.”

“Around that time,” continued Jog, “the Chief Minister announced that Sainik schools would be set up in every district. I jumped at the opportunity, but all I could muster was Rs 11,000. I went about collecting every tiny contribution — nothing was too small for this cause. At last, I was able to get a residential school to start in the Chikaldara sub-division, some 100 km from Amravati. Thereafter, I persuaded every Chief Minister to make a donation and the school could expand and finally move up to the Class 12 stage. It has now completed 22 years, has nearly 300 boarders and has a 100 per cent success rate.”

This story becomes heartrending when one realises that Chikaldara falls in Melghat subdivision, which records one of the highest rates of malnutrition in the country. As recently as August 2013, the Times of India headlined more than 400 deaths in Melghat from malnutrition (confirmed by government statistics).

Jog had another passion, rainwater collection. A small investment on the hostel roof had performed miracles. He pursued the idea with the dream of resurrecting the orange orchards of Amravati that once stood second only to the famed oranges of Nagpur. He tells of how he looked for support from Oxfam, NABARD and the Aga Khan Foundation, but all his letters of entreaty met with failure. But when his mission seemed doomed to collapse, it was the Council for the Promotion ofApplied Rural Technology (CAPART) which proffered support. Soon the village wells and tanks began brimming with water. But his dream of reviving the orange country was not to be: the villagers decided to grow vegetables instead to rake in Rs 50,000 a year in preference to a five-year wait for the orange trees to fruit.

This policeman-turned-farmer friend was also a great advocate of the check-dam strategy. But not everything he touched became a success. Jog pursued the local MP and MLAs to contribute, but not a single legislator parted with even one rupee for a scheme which could have provided a perennial source of water to the villages. Although a government resolution was passed making it a model scheme, disappointingly, when the officers changed the scheme went into disuse. The story only reinforces what we see happening time and again.

FOR some more years Jog continued to find ways of fulfilling his passion for giving back something to his beloved Amravati. In the meantime, his second son had joined the Indian Police Service and was posted as the DCP (Crime) — one of the key assignments in the police setup in Mumbai. But, with not even a hint of what was to come, he suffered a severe cardiac arrest and died instantly. Living as he was in Amravati, Jog could only reach Mumbai in time for his son’s funeral. This was the third calamity that Jog had to contend with in less than 10 years.

When one talks to the man, there is no sign of bitterness or remorse. No complaints about God’s ways. And unlike so many who take sympathy and support for granted, even afterso many years he is grateful that the then Chief Secretary of Maharashtra spontaneously asked him to continue to live in his son’s official house for as long as he needed to. In less than two years Jog left the house, carrying with him the responsibility for his son’s widow and two fatherless grandchildren.

Very recently Jog was hospitalised in Amravati due to an illness. At 87, he is a shadow of his former self. But even so he has this to say: “Your life is not a bed of roses. The roses also have thorns. One’s life will always have ups and downs. One has to face them with courage; suffer the unfortunate tragedies of life with fortitude and carry on to the best of one’s ability.”